|

|

Carter’s award thrills local historian

|

|

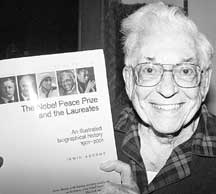

Irwin Abrams

|

As the world watches

on Dec. 10, the city of Oslo, Norway, will come alive with festivities

in honor of Jimmy Carter, the recipient of this year’s Nobel Peace

Prize. Following the afternoon awards ceremony, Norwegians will take to

the streets in a torch-lit procession as the winner waves to the crowd

from the balcony of the Grand Hotel. Later, a select group of guests will

join Carter at a banquet in his honor.

Throughout the festivities, perhaps no one will be more thrilled for Carter

than local resident Irwin Abrams, who has served as the Nobel Peace Prize

historian for 20 years. While attending the awards ceremony is always

exciting for the 88-year-old retired Antioch College professor, this year

Abrams has a special reason to celebrate — the man he has been nominating

for the past 11 years finally brought home the prize.

“Jimmy Carter is a man of moral stature, a spiritual force,”

said Abrams in an interview last week. “In these materialistic times,

he’s what the world needs.”

In his nominating letter to the Nobel Committee, Abrams said, “I

have nominated Jimmy Carter for the prize every year since 1991, convinced,

as I wrote to you in my letter last year, that ‘his qualifications

are indubitably the equal of many of the Committee’s celebrated choices

in the last hundred years.’ ”

In his letter, Abrams cited Carter’s achievements as president, including

his 1978 Camp David mediation between Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Menachem

Begin of Israel and his successful negotiation of nuclear arms agreements

and the Panama Canal Treaty. Most important, however, are Carter’s

post-presidential achievements in peacekeeping and human rights, said

Abrams, quoting the former President as saying, “I am more committed

than ever to waging peace, fighting disease and building hope around the

world.”

Abrams bristles at the recent press emphasis on the selection of Carter

as the Nobel Committee’s “kick in the leg,” (the Norwegian

version of “slap in the face”) to the Bush administration’s

proposed war on Iraq, an emphasis that some could see as taking away from

Carter’s worthiness.

“The award citation doesn’t mention Bush at all,” said

Abrams, “and that’s the only document that the whole committee

has to approve.”

The world will never know what took place in this year’s award selection

process, Abrams said, because the committee selections take place in private,

and the committee — five members selected by the Norwegian parliament

every six years — does not take minutes of its process.

Although the secrecy of the Peace Prize selection process seems a “crazy

way to run a railroad,” Abrams said, he believes the end results

have, overall, been positive.

“I think over the years they’ve done a good job implementing

Norwegian values,” Abrams said. Overall, he said, Norway tends to

be a liberal, humane country that, per capita, gives more aid to developing

countries than do other countries.

What is known is that, when considering potential Peace Prize laureates,

the Nobel Committee meets “under a candelabra in a 19th century building,”

said Abrams, surrounded by portraits of previous Peace Prize winners.

“All the previous winners are on the wall” and presumably set

a good example, said Abrams.

The Nobel Committee picked Carter from 156 valid nominees, including 39

groups and 117 individuals, Abrams said. Those eligible to nominate candidates

include governments, legislators, members of international courts, previous

winners and university professors of history, political science, philosophy,

law and theology.

“Someone wants to nominate me,” said Abrams with a smile. “Happily,

she isn’t eligible.”

The case could be made, though, that Abrams has done a considerable amount

to promote world peace. When he was approached 20 years ago by the publisher

G.K. Hall and Company to write a history of the Nobel laureates, Abrams

had retired from a long career teaching history at Antioch College and

had another project in mind. But he reconsidered his project, influenced

by a survey he encountered at that time listing young people’s heroes.

Those heroes, mainly rock stars and actors, left Abrams, a longtime Quaker,

longing to provide young people with more substantial role models.

So he agreed and set about his long-term project of writing biographies

of each Nobel Peace Prize winner.

A centennial edition of that history, The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates,

is currently available at Sam & Eddie’s Open Books in Yellow

Springs.

As the Peace Prize historian, Abrams has been interviewed by many members

of the national media, including CNN and The New York Times, since Carter

won the prize.

He has never regretted his 20 years spent researching, and in many cases

interviewing, the Nobel Peace Prize nominees, Abrams said.

“I get educated every time,” said Abrams of each year’s

awards. He said Nobel awards of recent years have brought the world’s

attention to little known human rights conflicts in such places as East

Timor, the home of 1996 Peace Prize winners Carlos Belo and José

Ramos-Horta .

“The world had never heard of this half an island under Indonesian

rule where people were being mistreated,” said Abrams. “The

Nobel prize gave recognition to their independence movement, and now they’re

independent. The Peace Prize played an important role.”

Over the years Abrams’ work has also provided him with countless

role models of men and women who live lives of courage and faith, the

two attributes he finds most laureates share. While some, like Jimmy Carter,

Dr. Martin Luther King and Albert Schweitzer, expressed a profound religious

faith, many, such as Linus Pauling did not, said Abrams, but they did

share a faith in humanity.

“They had to have that faith,” he said, “because they met

an awful lot of obstacles.”

After finishing the latest edition of his book, Abrams felt he had completed

his 20-year project. But recently, he said, he was contacted by his publisher

about adding a new section on the 2002 selection of Carter as Nobel laureate.

“I felt that I’d done my book and should be able to relax,”

Abrams said of his first response to the publisher. But then he considered

the possibility of writing about, and possibly interviewing, the man he

had wanted to win the Peace Prize for more than a decade.

Abrams smiled and shrugged, and it seemed clear that perhaps his work

isn’t yet finished. Regarding the offer from his publisher, Abrams

said, “He set my mind spinning.”

—Diane Chiddister

|